COMIC FOUNDRY INTERVIEW WITH PAOLO RIVERA

You went to the Rhode Island School of Design, right? What did you learn there that made you a better artist?

Yes, class of 2003 (Go Nads!) Most of the things that I "learned" while there, I didn't really come to understand or explore until later— I hear that's fairly common (and not exclusive to art school). The most important thing is to be exposed to as many different things as possible, while maintaining a personal focus that grows out of your own interest and passion; that way you don't limit yourself, but also have something to show for your four years at school. Oh yeah— and life drawing is the best practice.

What did you learn from having David Mazuchelli as a teacher?

He was the first adult (especially in the academic world) to formally recognize the importance and potential of comics. Completely disregarding my partiality for the subject matter, he was also the best teacher I had at the school. In fact, I was essentially ignorant of who he was until I was in his class. Although draughtsmanship was not a major component of the class, it was informed, like many aspects of image-making, by his careful, analytical approach to making comics. My decisions became more considered under his guidance, and my artwork, for the first time, became concerned with more than just perspective and anatomy.

You live with fellow comic artist R. Kikuo Johnson. How does that roommate dynamic work? In terms of feedback for each other?

Um... he doesn't clean bathrooms. Besides that, he has become one of the biggest influences in my comics life. His passion for the medium is contagious (and so are his philosophies and tastes). In a more practical sense, he's always there to bounce ideas off of, he has a vast library of comics that's always at hand, and we tend to use each

other as models.

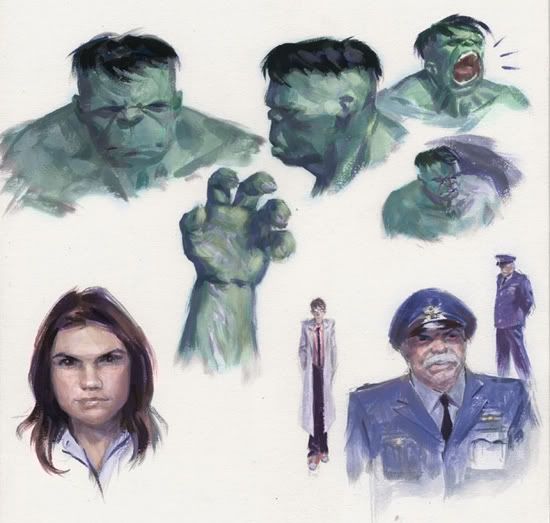

Your X-Men Mythos already hit stands and you've got a few more coming out as well. What was the biggest obstacle in painting so many characters?

It's technically difficult, and quite time consuming, but most of these characters already exist in my mind in a particular way. When I'm given an assignment, I already have a sense of what, for instance, the Hulk should look and move like.

What's the hardest part about painting for comics?

Wanting to do black and white art, but not being able to... for now.

Regarding your decision to give up oil painting, is this a financial move? A productivity move? A creative one?

There were actually several different reasons for the switch, but I'll readily admit that the financial pressures made it a necessity. I had contemplated it many times, but was never really forced to before. The other reasons range from storage to health issues. For example, a 23-page comic takes up a lot of room in a Brooklyn apartment if they're each 16" x 24" on hand prepared, heavy wood. And since I sleep where I paint, I've been breathing some pretty nasty vapors for the past 2 years.

What's the time saved on switching painting styles?

Right now, I'd say it's about half the time, but I'll get even faster as I practice. This was another major reason for the switch. I worked pretty hard in 2005, but don't feel like I have anything to show for it. I made one comic in all of last year and that's not acceptable, creatively.

So then, what's the process on your new style?

Once I've penciled a page out on 8" x 12" bristol board (Strathmore series 500 4-ply), I paint it using black and white Holbein's Acryla Gouache (fancy name for matte acrylic) in a series of nine mixed gray values. Once finished, I scan it in and color it in Photoshop, using a separate layer set to "color" mode. This allows the brightness values to show through while changing the hue and saturation of the resultant colors. To get slightly technical, this means that I don't use pure white since only a gray value, however light, will allow a color to replace it. For example, in a black and white photograph, the only pure white appears in overexposed areas and some highlights.

How does going to digital color affect your work? Did you have to learn anything new to achieve the desired result?

I think it will have the same general feel as the oil paint, but will reproduce better and, therefore, be much more legible. I'm actually using many of the same techniques that I utilized to bring my oil paintings to press. This was yet another reason for the switch: I was spending as much time at the computer (trying to get the paintings to look like faithful reproductions) as I did at the easel.

What will be your first book in this new style?

Mythos: Hulk

Would you rather be a cover artist? Or do you prefer to do interiors?

Cover work is attractive because it is less work (in comparison) and the rewards are often greater, but I actually prefer interiors. They're ridiculously challenging and, ultimately, more fulfilling.

What's the one thing/person that you've had the hardest time capturing in paint?

It's all pretty darn hard. If I had to narrow it down to a particular subject matter, it might be "large, detailed, interior spaces." I suppose that covers quite a range of things, but I think that's precisely why it's so difficult. A big part of this is solved, however, by switching my working methods. Keeping in mind the "big picture" with regard to color can be difficult when there are more objects in a composition. By coloring digitally, it's much easier to make things work as a whole while still paying attention to detail, since it's so easy to edit.

What's the most important thing you've learned since entering the comics industry?

Personally, it's that I shouldn't paint comics in oil— a lesson from which I am already reaping the benefits. In a broader sense, I've learned that composition and gesture are becoming my most important tools for communication in the medium.

1 Comments:

I like this pic!

Regards

custom gates

Post a Comment

<< Home